Audience Note

This document is written with BBEdit package developers in mind; it assumes a working knowledge of Unix scripting and common command-line conventions, as well as a working knowledge of Xcode's nib editor (Xcode 4 or later).

You won't have to write any Cocoa code, but working knowledge of Cocoa bindings (which generally goes with knowing how to edit nibs in Xcode) is a strong plus -- we will not attempt to explain the concept of bindings here.

Using nibs for #! script parameters

BBEdit 11.0 introduces the ability to construct simple modal-dialog interfaces for #! scripts, so that the user can decide at runtime how the script is to be invoked. The interface is completely data-driven: no compiled code is used (though if you wish, you can write a compiled executable instead of a #! script and use the information in this document to create a dialog-box interface for it).

Table of Contents

This document describes the following basics for creating a #! dialog box:

Constructing the Nib

In general, constructing a dialog box for a #! script is pretty straightforward. There are some special considerations, because (in Cocoa terms) the controller class doesn't really exist as far as the nib knows; and from the application side, since the dialog box exists in a vacuum, some specific hints need to exist in order to properly bind the controls to argument values when the user runs the script. Finally, there are some limitations -- specifically, not all Cocoa control types are supported. (Or, put another way, controls which are supported must share a specific behavior.)

Setting Up the Window

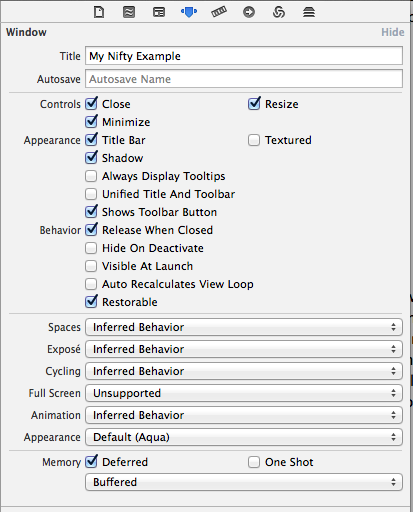

The window should be a basic Cocoa document window. It may be resizeable (or not) as you wish, and its settings should be as illustrated:

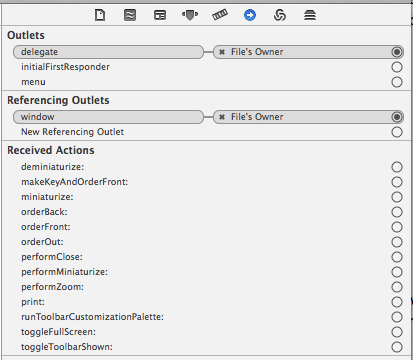

The window should have its delegate and window properties both bound to the File's Owner:

Binding Controls to Arguments

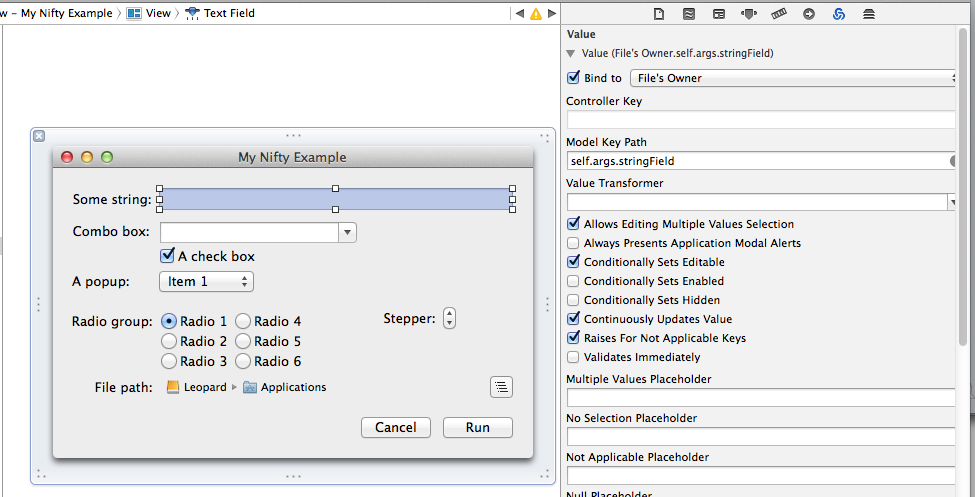

The controller class that BBEdit uses to run the dialog box contains a dictionary of argument names and values. This dictionary's key path in the controller is args; so to bind values from a control to a value in the dictionary, bind the control's value to File's Owner.self.args.<argument name>, where "<argument name>" is the actual name of the argument passed on the command line. Here's a screen shot to illustrate:

This is the binding for an argument named "stringField". As discussed, the edit field's value is bound to the self.args.stringField key path in the file's owner. Thus, when the edit field is changed, the internal value changes as well, and when you click the "Run" button, whatever's entered in the edit field will be passed to the #! script as -stringField <some string>.

Note: The correctness of the bindings is not checked at runtime; so if you set the bindings up incorrectly, the argument names will be generated incorrectly (at least) or an AppKit exception may occur which prevents the dialog box from running (at worst).

The dialog box interface is intended to pass through values for which there is a single representable string value (including numbers and file paths) and Boolean flags to the script's command line. Thus, you can use only the Cocoa controls that can be bound to a single (string, numeric, or Boolean) value. File path controls don't strictly meet this definition, but are nonetheless supported as well. Table views, outline views, and other such are not supported, nor is there any provision for custom views.

The basic set that have been tested and are explicitly supported are:

- Text field (

NSTextField) - Combo box (

NSComboBox) - Check box (

NSButton, check box) - Popup menus (

NSPopUpButton) - Radio groups (

NSMatrix) - Steppers (

NSStepper) - File paths (

NSPathControl)

A Note about File Paths

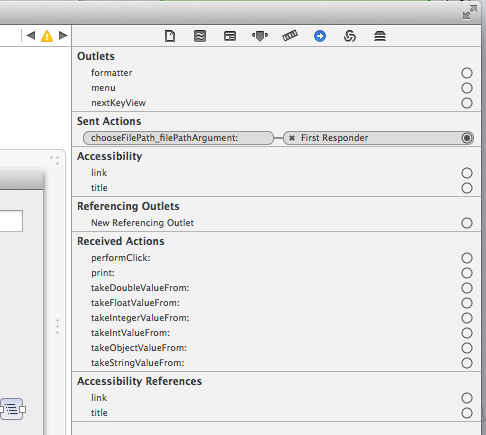

File Paths (NSPathControl) are bound to arguments in the same fashion as other single-value controls. However, a path control by itself isn't terribly useful; you will typically want to provide a button to let the user choose a file. That button in turn needs to be associated somehow with the file path control. We accomplish this by associating the button's sent action with the argument being manipulated, using a simple naming convention: "chooseFilePath_" followed by the name of the argument. So in our example, given a path control bound to an argument named filePathArgument, the button's sent action is "chooseFilePath_filePathArgument":

This action is attached to the first responder; and when the user clicks that button, they'll get a file panel, and when they choose a file, the path control whose value was bound to filePathArgument gets updated.

Action Buttons

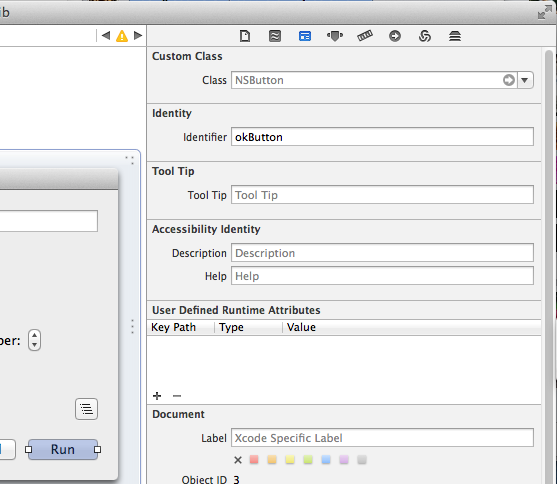

Apart from action buttons for manipulating path controls, only two action buttons are supported: the "do it" (OK/Run/etc) button, and the Cancel button. There should be one of each type in the dialog box. Rather than binding these buttons to a specific action, BBEdit figures out which is which based on their "Identifier" property in the nib editor:

For the "do it" button, set its identifier to okButton.

For the "Cancel" button, set its identifier to cancelButton.

Customizing argument behavior

Command-line tools and scripts don't follow a unified model for argument passing. By default, BBEdit will pass through arguments using what we refer to as the "standard" syntax: the argument name preceded by a dash, followed by the argument value, e.g. -stringField foo. In this form, the -stringField and the foo appear as two distinct entries in the incoming argument list (argv in the nomenclature of Unix command-line tools). If this is all you need, then you are all set -- no further work is required.

However, if you need additional flexibility, you can create an outboard property list file containing information about each argument that requires special treatment. (The location and naming of this file are described below.) If the property list is present, BBEdit will use the information it contains to customize the argument format.

The following argument forms are supported:

| Name | Argument Form | Behavior |

|---|---|---|

StandardFlag | -a (as in ls -a) | if YES, include; otherwise omit |

VerboseFlag | --help | if YES, include; otherwise omit |

ExplicitFlag | -x={YES,NO} | meaningful for Booleans only |

VerboseExplicitFlag | --someFlag={YES,NO} | meaningful for Booleans only |

StandardArgument | -arg value | |

VerboseArgument | --arg value | |

StandardAssignment | -arg=value | |

VerboseAssignment | --arg=value | |

EnvironmentVariable | arg=value | set in environment, not passed on command line |

Some notes:

- If there is no entry for the argument in the property list,

StandardArgumentis used. - String values (including file name paths) are not escaped or quoted in any way.

To demonstrate the construction of the arguments plist file, here is an example for a hypothetical #! script, which takes arguments named stringField, comboBoxValue, aCheckBoxFlag, popupSetting, and filePathArgument:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>stringField</key>

<dict>

<key>ArgumentType</key>

<string>StandardArgument</string>

</dict>

<key>comboBoxValue</key>

<dict>

<key>ArgumentType</key>

<string>VerboseArgument</string>

</dict>

<key>aCheckBoxFlag</key>

<dict>

<key>ArgumentType</key>

<string>VerboseExplicitFlag</string>

</dict>

<key>popupSetting</key>

<dict>

<key>ArgumentType</key>

<string>StandardAssignment</string>

</dict>

<key>filePathArgument</key>

<dict>

<key>ArgumentType</key>

<string>VerboseAssignment</string>

</dict>

</dict>

</plist>

Where things live on disk

As described in chapter 2 of the user manual, scripts (including #! scripts and compiled executables) live in Application Support/BBEdit/Scripts/ or Application Support/BBEdit/Text Filters/ (and the parent of Application Support may either be your ~/Library/ or your main Dropbox folder).

To provide a dialog interface for a #! script or executable, BBEdit will always look for a folder named Resources which is a sibling of your script's parent folder. (In command-line terms, this would be ../../Resources.) In the Resources folder, BBEdit will look for a .xib file whose base name matches the base name of your script or executable. So, if you have (for example) a script named TidyCommands.py in the Scripts or Text Filters folder, BBEdit will look for Application Support/BBEdit/Resources/TidyCommands.xib. Or, in command-line nomenclature: ../../Resources/TidyCommands.xib.

If you have a plist for customized argument behaviors (see above), BBEdit will look in the Resources folder for a property list file whose name is constructed using the base name of the file, with "-arguments" added, and a filename extension of "plist". So, if your script's name is (for example, again) TidyCommands.py, BBEdit will look for Application Support/BBEdit/Resources/TidyCommands-arguments.plist, and if it is present, use its contents appropriately.

Putting things in the main Application Support folder works, and is fine if you're doing something for yourself (or just prototyping). However, if you're planning to release something else for others to use, you must not instruct users to place items loose in the main Application Support folder. Instead, construct a BBEdit package (see chapter 15 of the user manual) and arrange the items appropriately within the package, with the script(s) in the package's Contents/Scripts/ or Contents/Text Filters/ as appropriate, and the nib and (optionally) arguments files in Contents/Resources/.

A Note about Compiled Nibs

In order for a nib to be usable by an application, it needs to be compiled. Xcode ordinarily does this as part of the build process; but in this case, you aren't building an application, so the nib never gets compiled. In order to ease the development process, BBEdit will compile nibs on the fly as necessary. Since you need Xcode to build the nib in any event, the necessary tools to compile the nib are present on your machine, and this is no problem.

However, if you are sharing your packages with others, you cannot rely on them having the developer tools installed; nor should you require them to install the tools. To resolve this, you must compile your nib before releasing it. The command line to do this looks like:

xcrun ibtool /path/to/original/nib --compile /path/to/compiled/nib

Note that you should never overwrite your original, or else you won't be able to modify it.